Visible Work, Lasting Systems

I’ve worked in documentation full-time for more than fifteen years. The one constant is that it never really ends. Whether it’s a help article, a training guide, or a standard procedure, the real value appears only after people start using it. They click through, ask questions, and reveal what you couldn’t see while building. It becomes useful at the point where it meets the mess of real life.

Most of how I work now grew out of learning to handle feedback that wasn’t always comfortable.

Early on, one manager gave notes on everything I touched. Every version came back marked up. If I asked her to focus on the technical side, she turned to tone or formatting instead. Eventually, I stopped trying to predict her comments and focused on moving faster. That’s when I realized overthinking slows progress more than critique ever could. The version in my head was never going to match hers.

Later, I worked under someone who didn’t want to see drafts until they looked finished. To get feedback before I was too far in, I started making simple visuals early. It gave him something solid to respond to. Once he saw it, we could align quickly and keep going.

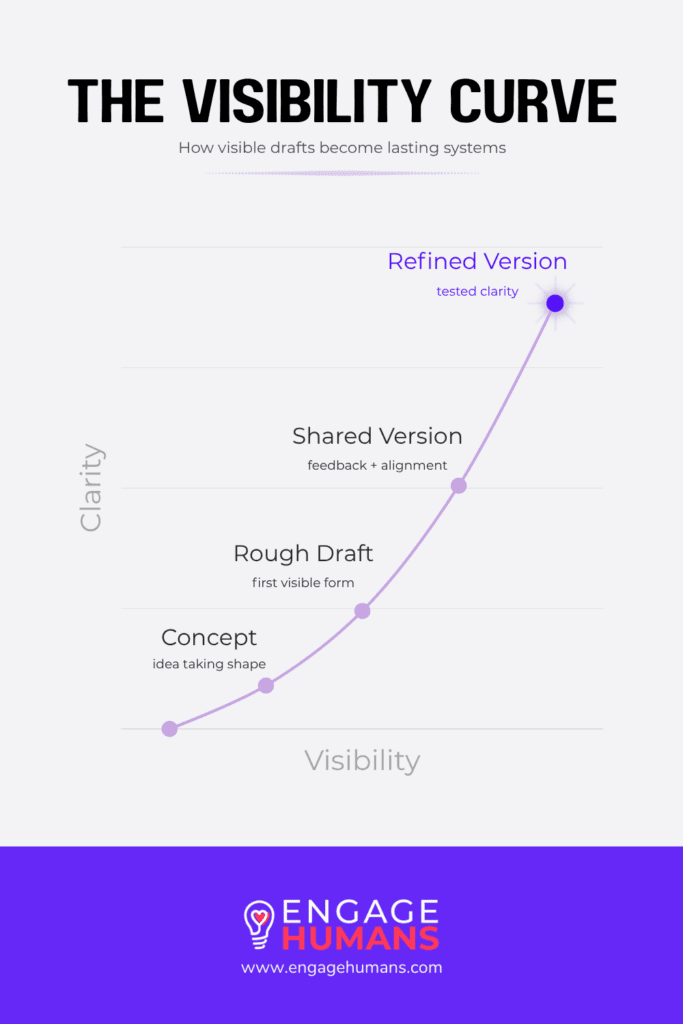

Those two lessons shaped everything I do. One taught me the importance of showing work before it’s fixed in place. The other showed me that people often need to see something to understand what they mean by feedback. Together, they became my baseline: start small, share early, and let clarity form as people react.

Why Visibility Matters

Most teams begin with clear intentions. They want structure, consistency, and documentation that can scale. The slowdown happens when that structure comes too soon. Layers of templates and approvals build up before anyone knows which ones actually help. The order they were trying to create starts creating drag instead.

It’s easier to start with visibility. Let people see what’s being built while it’s still forming. When they can see it, they can participate in shaping it. I wrote more about this in Minimum Viable Products and “Mid” Drafts, where I explored how unfinished work brings clarity faster than any polished draft.

This approach has two moving parts that support each other.

The Process

Define → Build → Share → Iterate

The Stack

Website → One-Pager → Getting Started Guide → FAQ → Video → Tracker

The process keeps momentum. The stack captures what’s learned as it happens. Each document grows out of the one before it. A brief guide can become the start of a help center. Over time, that help center might turn into a full training system.

How It Looks in Practice

Every documentation project starts differently, but my first move rarely changes. I make something visible, even if it’s rough.

Take a new client feature. The old way might involve a long discovery period, outlines, and a draft weeks later. By the time feedback arrives, it’s vague: “This isn’t what I pictured.”

Now I skip ahead to something concrete. Sometimes, it’s a single Google Site page that shows how navigation might work. Other times, it’s a short walkthrough capturing the basic flow. The first version is rarely right, but it gives everyone something real to respond to.

When I built the first version of the Starting Over site, the client couldn’t articulate what he wanted until he saw it. My first attempt at navigation completely missed. But once it existed, he could point to what didn’t feel right and describe what did. That first pass gave him words for his ideas and gave me direction for the next round.

That’s how most of my projects unfold. The moment the work becomes visible, the conversation changes. Clarity grows from reaction, not from planning alone. Each draft teaches something about what holds up and what doesn’t, long before polish enters the picture.

Once the first version finds its footing, I build outward. A page turns into an onboarding guide. A guide expands into a help center. A help center becomes a training system. Each stage refines what was already tested and proven.

How This Differs from the Usual Workflow

This isn’t Agile, design thinking, or docs-as-code. It borrows what’s useful from those worlds but doesn’t rely on any single method. I wrote more about this in ADDIE and the Reality of Instructional Design, where I talked about keeping the process practical.

A lot of frameworks aim for better production speed or polish. My focus is on comprehension and how quickly people grasp what’s in front of them. The goal isn’t faster perfection. It’s faster to understand, for both the writer and the reader.

Documentation often gets treated like a production task, something to check off when a release is done. I see it as a learning process that keeps reshaping itself as people interact with it. The change happens because the work is seen and discussed, not because a workflow status flips from “In Progress” to “Review.”

Start Small, Let It Grow

This approach isn’t about cutting corners. It’s about focusing effort where it matters most. Each stage builds on the last: defining gives direction, building exposes weak points, sharing invites better language, and iteration sets the pattern for what works.

When documentation becomes visible early, it stops feeling like an afterthought. It becomes part of how the product itself takes shape.

Good systems don’t come from blueprints. They come from visible progress that earns its place over time.

A page becomes a guide.

A guide becomes a system.

And eventually the habit itself does the work.

Closing

Clarity isn’t something that arrives at the end; you layer it in as you go. The more visible the work, the sooner you find it.

If you want a starting point for your own process, look at The Docs Every Startup Product Needs. It’s a simple way to see how this approach works in practice.